The Modern Challenge Faced By Processors

Modern processors are extraordinary feats of modern engineering. Billions of transistors, blistering clock speeds, multi-core architectures, all designed to crunch data faster than ever before. What used to take entire rooms of equipment can now be all embedded within a single chip measuring just a few mm across.

But for all their raw power, processors face a fundamental bottleneck: the separation between compute and memory. No matter how fast the CPU runs, it must constantly wait on data to be fetched, moved, and cached. That’s why multiple layers of caches exist, to hide the painful latency between memory and processor. Yet as applications grow, those caches can’t always keep up, and the gap between computation and data access widens.

This dependency on caches and buffers is far more than a minor inconvenience. In real-time workloads, such as AI inference or direct memory access (DMA) operations, the distance between the CPU and the data source can cripple performance. Computation that happens far away from where data lives means that modern processors can spend as much time waiting as they do working.

However, in recent years, the industry is shifting toward RISC-based designs, simplifying instruction sets and focusing on efficiency. But even with that shift, the architectural question looms larger: do we need to rethink how processors are built? Should future chips integrate memory and compute more tightly to remove latency altogether?

XCENA’s MX1: Thousands of RISC-V Cores Bring Compute Closer to Memory

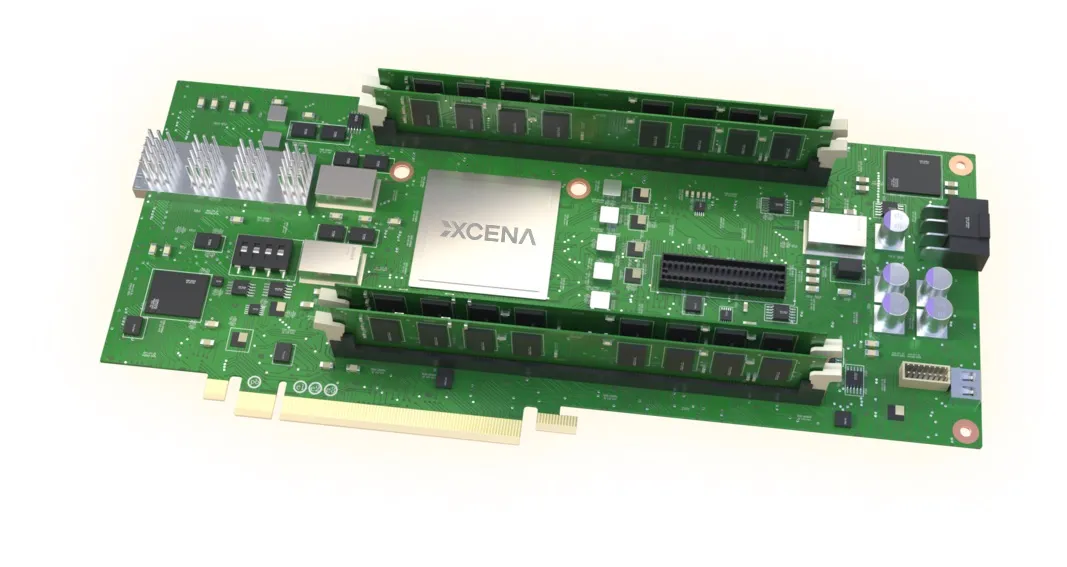

Recognizing the challenge that modern processors face when working with memory, South Korean startup XCENA has unveiled a potential solution: the MX1 computational memory chip, designed to bring compute directly next to DRAM. The MX1 packs thousands of custom RISC-V cores, with the goal of handling memory-heavy tasks such as vector database operations, analytics, and AI inference. Built on PCIe Gen6 and Compute Express Link (CXL) 3.2, the chip leans into near-data processing, an architectural shift that reduces CPU-memory latency and improves throughput. By placing compute where the data lives, the MX1 could change the way future servers are built.

In addition to raw processing, the MX1 also supports SSD-backed expansion, enabling petabyte-scale capacity while integrating compression and reliability features. So far, XCENA has two models planned: the MX1P later this year, with samples shipping to select partners in October, and the MX1S in 2026 with dual PCIe Gen6 x8 links. Both are designed to exploit the higher bandwidth and flexibility of CXL 3.2.

The chip has already earned recognition, winning “Most Innovative Memory Technology” at FMS 2025, following XCENA’s “Most Innovative Startup” award in 2024. To encourage adoption, XCENA is providing a full software stack, including drivers, runtime libraries, and development tools so engineers can evaluate MX1 in environments ranging from AI to in-memory analytics.

Are 1000-Core CPUs the Answer?

As workloads grow increasingly parallel, the idea of processors with thousands of cores is moving from concept to reality. Modern computing tasks need far more than raw single-thread performance, they also need the ability to juggle countless lightweight tasks (often in real time). Thus, a 1000-core CPU could be the natural fit for this shift, especially in servers and data-heavy environments.

The logic behind such a concept fits in with the fact that most modern tasks are highly parallelized. For example, AI inference, database queries, and analytics all split neatly into many small jobs that can run side by side, and packing thousands of cores into a single device gives hardware the parallel horsepower to match these demands.

But this concept isn’t without its own set of challenges. Backwards compatibility, for example, weighs heavily on processor design, and legacy software is rarely written to scale across hundreds, let alone thousands, of cores. At some point, new architectures will have to abandon the baggage of older systems and fully embrace parallel-first designs.

So while high-core-count server chips look like an incremental improvement, they may represent something bigger, a turning point where compute architectures evolve to meet the realities of modern workloads. The question is less about whether 1000-core CPUs are possible, and more about whether the industry is ready to leave the past behind.