The Rising Energy Cost of AI and Computing

On paper, computing becomes more efficient every year, with transistors shrinking, leakage improvements, switching energy droping, and architects squeezing more work out of each clock cycle. Energy per operation also trends downwards, just as it has for decades. If you only look at individual devices or isolated benchmarks, the story appears reassuring.

In reality, total energy consumption tells a very different story. The computing market as a whole is using more power than ever, and the curve is still pointing up. The reason for this comes down to scale. Modern systems are denser, workloads are heavier, and deployment volumes are exploding faster than efficiency gains can offset. What we save per transistor, we lose many times over by deploying vastly more of them.

Data centers are the clearest example of this rapid rise in energy consumption. Computational capability has increased dramatically, but so has the resulting overall energy consumption. Racks are denser, facilities are larger, and cooling infrastructure has become a first-order design constraint as opposed to an afterthought. Power budgets that once supported an entire facility now disappear into a handful of AI racks, and energy efficiency improvements at the silicon level are simply being overwhelmed by demand.

And of course, AI has done anything but helped this energy amplification problem. These workloads are massively parallel, data-heavy, and persistent. They run continuously, not sporadically, and they scale aggressively with model size. Traditional computing architectures, where services occasionally use CPU and scale as needed were never designed for this new kind of workload. Moving large volumes of data back and forth between memory and processors is expensive in both power and time, and AI workloads do that constantly.

GPUs have dramatically helped in power consumption, but they are only a partial solution at best. They improve throughput per watt compared to general-purpose CPUs, but they are still fundamentally constrained by memory movement and digital arithmetic overhead. Anyone who has looked at the power draw of modern AI accelerators knows that efficiency gains are being bought with brute force rather than architectural elegance (i.e. through custom silicon that is specifically designed for AI applications).

If computing is going to continue scaling, especially for AI, incremental improvements are no longer enough. What is needed are fundamentally different architectures that treat energy as a primary design constraint, not a side effect. That is where new memory-centric approaches start to matter.

Researchers Create New Memory Technology Offering up to 5000x Energy Efficiency

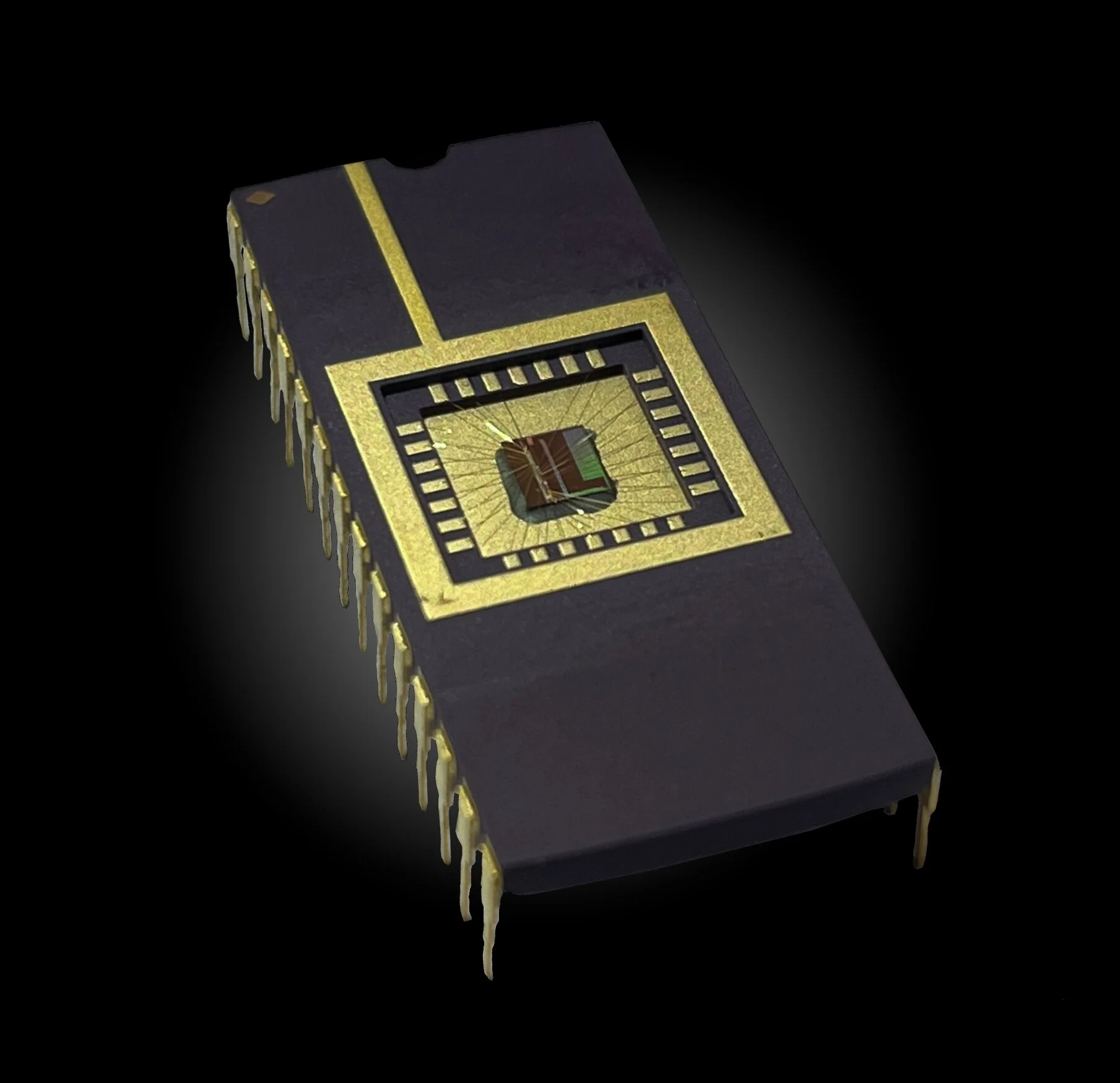

A research team at Politecnico di Milano, led by Professor Daniele Ielmini, has demonstrated exactly the kind of architectural shift that current trends demand. Their work, published in Nature Electronics with Piergiulio Mannocci as first author, presents a computing chip that dramatically reduces energy consumption by changing where computation happens.

The project is part of ANIMATE, an ERC Advanced Grant awarded in 2022, focused on Closed-Loop In-Memory Computing. The core idea is simple but powerful; conventional systems waste enormous energy moving data between memory and processors, so in-memory computing removes that bottleneck by performing calculations directly where the data is stored.

The chip, developed by the DEIB team, implements this concept using a fully integrated analogue accelerator manufactured in CMOS technology. At its heart are two 64 by 64 arrays of programmable resistive memory implemented with SRAM cells. These arrays don’t just store values, but participate directly in computation.

Analogue processing blocks, including operational amplifiers and analogue-to-digital converters, are also integrated on the same chip. This allows mathematical operations to occur inside the memory arrays themselves instead of needing to move data in and out. Thus, data stays where it is and is transformed in place.

The results of this development are incredible, with benchmark tests showing an accuracy comparable to conventional digital systems, but with far lower energy consumption, reduced latency, and smaller silicon area. In some cases, energy efficiency improvements reach orders of magnitude, with claims of up to 5000 times improvement depending on the workload.

Just as importantly, the work demonstrates that analogue in-memory computing can be built using industrially relevant CMOS processes, making this closer to practicality than a lab curiosity requiring exotic materials. The platform is compatible with existing fabrication techniques, which immediately changes how seriously it can be taken by industry.

Is In-Memory Computation the Future of Computers?

In-memory computing has existed as an idea for a long time, but it has rarely been practical. Traditional architectures treat memory as passive storage and processors as the only place where computation happens. Now that model made sense when processors were fast, memory was slow, and data volumes were manageable.

But fast forward to modern computing and that balance no longer exists. Many modern workloads, especially in AI, are dominated by large-scale operations on memory-resident data. These operations are often simple and repetitive, including matrix multiplication, accumulation, copying, and scaling with little or no branching. In those cases, the cost of moving data dwarfs the cost of computing on it.

More importantly, supporting such operations inside memory does not require overwhelming complexity. For small regions of memory performing well-defined tasks, the additional circuitry is modest compared to the energy saved by avoiding constant data transfers, and the Politecnico di Milano work shows that this can be done without sacrificing accuracy or manufacturability.

But there is also a broader architectural shift underway; the idea that all computation should be funneled through a single central processor is becoming increasingly outdated. Graphics moved to GPUs long ago, AI workloads are migrating to NPUs, and it is not unreasonable to imagine database processors, virtual machine accelerators, or application-specific execution engines becoming standard parts of future systems.

In these hardware accelerated systems, in-memory computing fits naturally. Of course, it is not a replacement for CPUs, but just another specialized tool, optimized for a class of problems where energy efficiency matters more than generality. As computing fragments into purpose-built architectures, memory itself becoming computational is a logical step.

Whether this specific implementation becomes mainstream remains an open question,as research prototypes often illuminate the path without defining the destination. What matters is that this work proves a very serious point; massive reductions in energy consumption are possible when architecture changes, not just transistor sizes.

Given the trajectory of AI and high-performance computing, that kind of change is no longer optional. It is encouraging to see research that does not just make computing faster, but makes it sustainable. That alone makes this work worth paying attention to.