The challenges with cloud AI in edge and embedded environments

Over the past few years, engineers have slowly learnt the hard way that cloud AI, for all its benefits and brilliance, doesn’t work well with edge and embedded designs. But why exactly is this the case?

The first issue that engineers have faced is that round trip latency between an embedded device and the cloud is too great, and this makes cloud-dependent designs unable to meet real-time requirements. For example, motion control in robotics could be improved with the use of predictive algorithms, but if the time taken between sensing motion, sending data to the cloud, receiving data, and then applying it is too large (tens to hundreds of milliseconds), then the resulting AI can be outright unusable.

The second major challenge faced by engineers is that as sensors improve in resolution and frequency, the amount of data being streamed is growing rapidly. In many cases, continuously streaming raw data like video, audio, radar, or vibration pushes bandwidth costs and network congestion beyond what many systems can tolerate. As such, trying to utilise cloud-dependent AI with embedded devices can see massive bandwidth costs, and not only does this hurt battery life, but can also cause congestion on networks.

The third challenge faced by engineers is that many embedded and industrial deployments operate in environments with unreliable, intermittent, or non-existent connectivity, making cloud-dependent AI fundamentally fragile. Any place that doesn’t have a decent internet connection will likely struggle with cloud-dependent AI, and this introduces the possibility of no connectivity at all.

The fourth challenge faced by engineers is power budgeting. Simply put, wireless transmission often consumes more energy than local computation, and this can be problematic for battery-powered and energy-harvesting devices. By keeping data locally and utilising local processing, energy consumption can be significantly reduced, but trying to do this with cloud-dependent AI is challenging to say the least.

The fifth challenge faced by engineers is data privacy and sovereignty. As technology continues to advance, governments and regulators around the world are introducing strict rules on how personal data is handled, and many restrict what data can leave their respective country borders. This is particularly important in sectors such as healthcare, automotive, and industrial settings. Thus, trying to send raw sensor data from embedded devices to a remote server outside of a specific region could carry serious penalties.

The sixth challenge faced by engineers is that AI models trained in the cloud generally require large amounts of computational resources, and trying to deploy these in embedded systems simply isn’t practical. Such models will often be far too large in memory footprint, require excessive power and thermal performance, and will likely be far too expensive.

Finally, debugging and validating cloud-dependent behavior becomes harder as failures may originate from the network, backend services, or model updates outside the engineer’s control.

Examples of how edge AI in chips is helping engineers

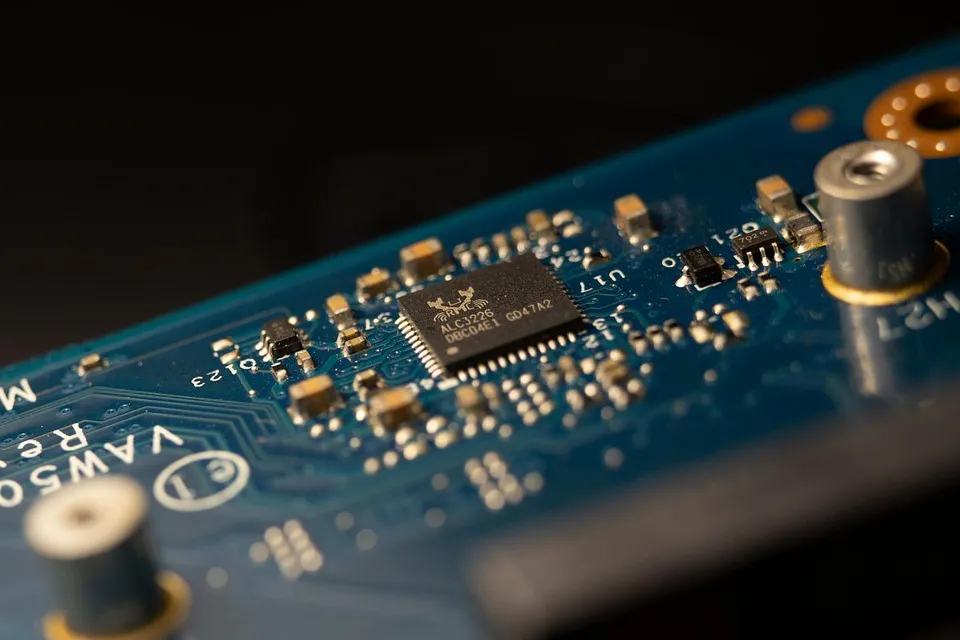

The first wave of edge AI chips have already hit the market, and engineers are already seeing the benefits of running inference directly on their edge chips, allowing sensor data to be processed locally with response times measured in microseconds (or a few milliseconds).

To stat, the ability for model optimization techniques such as quantization, pruning, and operator fusion to reduce the size of AI models has allowed engineers to deploy useful AI models in memory sizes ranging from kilobytes to a few megabytes. This reduction in memory size enables AI execution on low-end edge devices such as microcontrollers, which not only saves energy but also enables always-on operation through energy reduction.

Furthermore, the ability to run AI inference locally also allows for data privacy, something that is highly important in applications involving personal data such as user habits, biometrics, and location. The use of dedicated NPUs and AI accelerators in the latest edge AI chips is also enabling new designs to only send partial data to remote services, such as event streams, instead of raw data streams.

This usage of hardware accelerators significantly reduces the bandwidth needed to implement cloud computing and reduces operating costs while simultaneously improving privacy by not sharing raw data. Instead, a device can choose to transmit only events, classifications, or anomalies that have occurred, further simplifying the overall system architecture.

The deterministic nature of modern edge hardware, such as some Vision DSPs, is also proving to be highly beneficial for engineers. The ability to execute neural networks deterministically not only allows for strict timing guarantees, but also provides engineers with a high degree of certainty when designing their systems.

This is particularly advantageous in industrial applications such as automated warehouses and assembly lines where safety and repeatability are critical, in automotive applications where AI systems need to comply with strict safety regulations, and in safety-critical applications such as medical equipment where failure could result in serious harm.

Modern toolchains, such as those offered by TI, also provide a significant advantage by providing closer alignment between neural network design and hardware execution. Such tools enable engineers to create AI models that take full advantage of the underlying hardware, resulting in better performance and lower power usage.

Where could such technologies lead to?

Looking forward into the future, it is likely that over time, edge AI will become capable enough that it can operate autonomously for extended periods without relying on centralized cloud infrastructure. For example, engineers have already started to experiment with edge systems that collaborate together to share insights and models instead of raw data which not only helps to reduce bandwidth usage but also protect privacy. While such collaborative edge systems are still in their infancy, they may become mainstream.

It is also likely that the role of the cloud will change from making decisions to training, coordination, fleet management, and long-term optimisation. In other words, the cloud would take feedback from edge devices to refine its neural networks, provide updates to edge devices, and then use those updates to make further improvements.

With regards to hardware, there is a good chance that engineers will move towards more specialised hardware in the interest of performance. By far one of the biggest challenges currently faced by engineers is the increasing complexity of AI models, and the large energy and computational requirements needed to run them.

Thus, having a chip designed specifically for running AI algorithms on mobile platforms (such as smartphones) will allow engineers to eliminate unnecessary circuits that don’t contribute to the task at hand. This same concept could be taken even further with the development of specialised chips for vision, audio, motion control, and biosignals which would further improve performance.

Finally, if the current trend in privacy and regulation continues, it is likely that inference will be done locally on devices in favour of remote processing. As privacy is becoming a key selling point for consumers, devices that send raw data to remote servers will likely be looked down upon by customers, and this could come from either expectation or regulation.

Overall, the development of edge AI presents numerous opportunities to engineers, and edge AI could become a standard component of embedded design, much like connectivity and sensors are today. If things go well, we could see a whole new market open up around edge computing, and it is possible for entirely new product categories to emerge such as self-optimising infrastructure, deeply personalised devices, and intelligent machines that learn and adapt without the need for a remote service.