Apple Could Be Looking for New Foundries Other Than TSMC

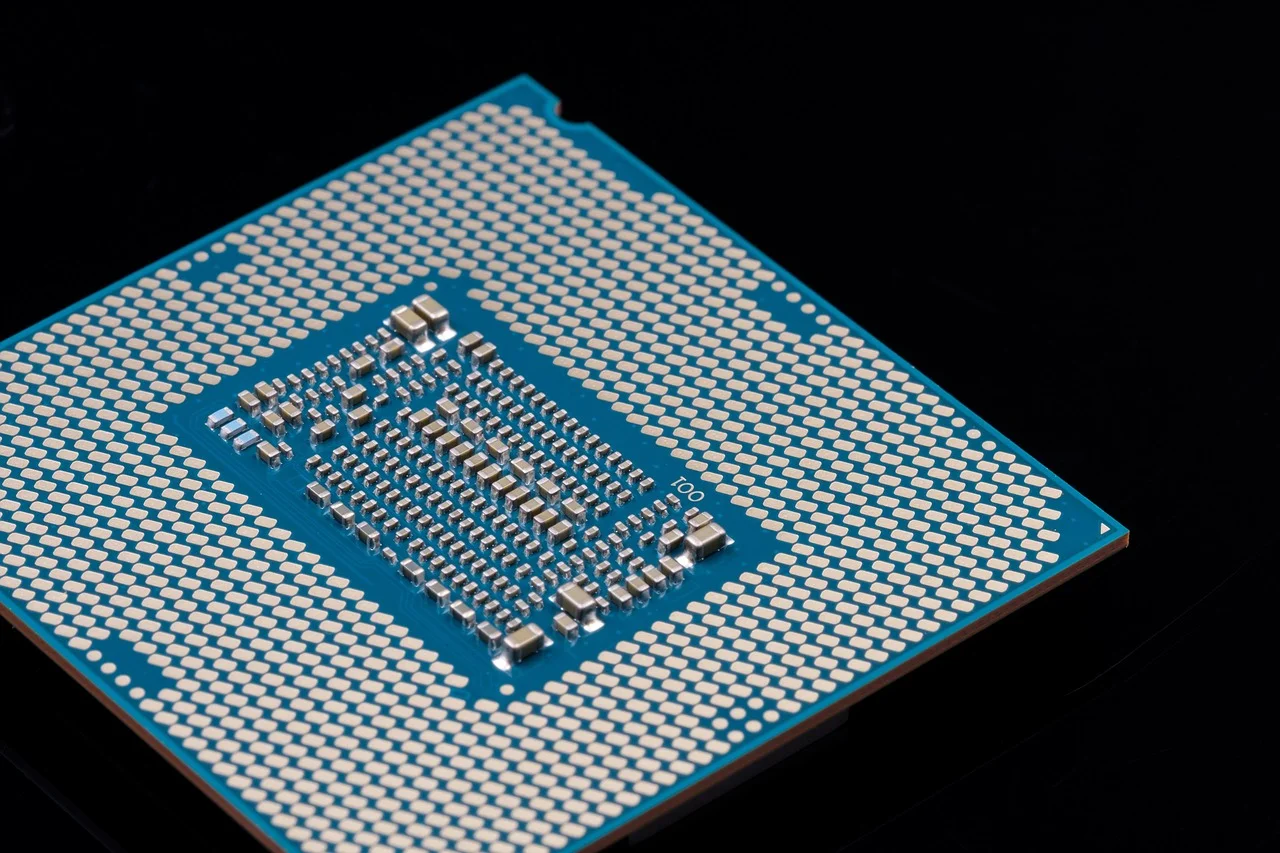

For nearly a decade, Apple’s silicon story has been tightly coupled to TSMC. Since 2016, every Apple-designed system-on-a-chip has come out of TSMC fabs, with Apple typically being first or second in line for new leading-edge nodes. That exclusivity, however, now appears to be under strain. According to reporting from The Wall Street Journal, Apple is now actively exploring whether some lower-end processors could be manufactured by foundries other than TSMC.

It appears that the motivation for this shift is manufacturing capacity, not performance, as a result of TSMC’s attention on the growing AI market. Compared to typical customers, AI accelerators are large, expensive, and ship in massive numbers to data centers, yielding massive profits. From a foundry perspective, these customers are incredibly attractive, but the consequence is that even major customers like Apple (historically TSMC’s most strategically important client), is no longer guaranteed preferential treatment across every product tier.

Of all the alternatives available to Apple, many have pointed to Intel as being the most plausible alternative, with several forecasts suggesting that Intel’s Foundry Services could begin manufacturing lower-end Apple processors around 2027 or 2028. Should Apple look towards Intel as a potential manufacturer, they would most likely use the fabrication service for producing lower end products, such as non-pro iPhones.

However, this move would not be a return to the Intel Mac era, as Intel would act purely as a fabrication partner, not a CPU vendor. Apple would still design its own cores, interconnects, caches, and accelerators, with Intel merely printing the silicon and giving Apple all the hardware freedom it needs.

What This Shift for Apple Really Means

Unlike many industrial processes, switching semiconductor foundry is far from trivial, requiring years of engineering, experimentation, and funding. While moving to a different plastic injection molding provider requires minimal checks and the transport of a new mold, each semiconductor process node comes with its own design rules, layout constraints, transistor behavior, and reliability characteristics. Thus, the same logic circuit implemented on two different processes can vary significantly in power, frequency, yield, and long-term stability.

Making matters more complex, foundry-specific standard cell libraries, SRAM compilers, voltage domains, and metal stacks all behave differently. Even minor differences in leakage or variability ripple through timing closure, power delivery, and thermal design. Porting a large SoC across foundries requires deep collaboration, extensive re-validation, and a willingness to accept that the result will not be identical.

That is why Apple even considering such a move is serious. Such a move implies a massive amount of pressure, so much so that it justifies massive engineering investment and long-term risk. Companies like Apple do not gamble lightly with their silicon roadmap, but if TSMC capacity constraints persist, other large customers will face the same dilemma. Eventually, it will get to the point where the industry as whole ca no longer rely on a single company to supply the majority of advanced logic.

Intel’s involvement, however, is particularly interesting. While Intel has lagged TSMC in recent process nodes, it remains one of the most experienced semiconductor manufacturers in the world. Many of the highest-performance processors ever shipped were built in Intel fabs, but the company’s problem has not been an inability to design or manufacture silicon, but a prolonged failure to execute consistently at the leading edge.

However, the situation between Apple and TSMC also disproves the assumption that access to the very latest node is mandatory for cutting-edge hardware. Performance, efficiency, and system capability increasingly come from architecture, packaging, and system-level optimization rather than transistor density alone. Apple’s own success with custom accelerators and tightly integrated SoCs already supports this view.

Why Older Nodes May Save the Day

There is a widespread belief in the industry that anything short of the latest node is somehow obsolete. This view, however, is completely wrong, and increasingly costly to the industry as a whole. Older process nodes remain perfectly viable for a vast range of modern electronics, with devices manufactured at 100 nm and below still being used across power management, analog interfaces, microcontrollers, sensors, and connectivity chips. Even in compute-heavy systems, not every function benefits from ultra-small transistors.

For perspective, older nodes are easier to manufacture, easier to scale, and deliver dramatically higher yields. They do not require extreme ultraviolet lithography systems that cost hundreds of millions of dollars per tool, and the result is lower capital expenditure, more predictable output, and far less fragility in supply chains. As foundries phase out these nodes in favor of bleeding-edge processes, they are effectively forcing the entire market into higher cost structures whether it needs them or not.

However, with some luck, pressures on newer nodes increase will see engineers turn back to older nodes. Such a scenario would create an major opportunity for the semiconductor industry, especially when combined with chiplet-based designs. Instead of forcing tens of billions of transistors onto a single monolithic die, multiple smaller dies can be fabricated on mature nodes and combined through advanced packaging.

Chiplets based on older nodes would face a number of issues, especially with latency and power consumption, but these challenges could be readily solved with careful design and layout. But the physical size of a chiplet package using older nodes can remain competitive, and individual chip die yields would improve dramatically compared to bleeding-edge nodes.

Looking further ahead, there is a credible argument that silicon fabrication could partially decentralize. Much like how 3D printing reshaped manufacturing expectations, smaller fabs focused on specific nodes and applications could re-enter the market. This would not replace emerging node fabs, but it would relieve pressure on them and reopen access to silicon manufacturing for smaller players.

If Apple use Intel (or any other foundry) for its next-generation of low performance chips, it doesn’t mean that older nodes will suddenly become popular, but it would certainly signal to others that using the latest technology is not always the best solution.