The Ending Era of EUV

When the semiconductor industry ran head-first into the limits of deep ultraviolet lithography, there were no elegant alternatives waiting in the wings. Feature sizes were shrinking, pattern fidelity was collapsing, and multi-patterning was becoming an expensive exercise in diminishing returns. At that point, the industry did not have choices, it had a singular problem, and only one company was willing, or stubborn enough, to attempt a solution. That company was ASML, and that solution was extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV).

EUV fundamentally changed what was possible for manufacturers. By moving to a wavelength of 13.5 nm, manufacturers could once again print smaller features without resorting to an ever-growing stack of correction tricks. Transistor densities increased, power efficiency improved, and Moore’s Law staggered forward for another generation. What is often forgotten, however, is that EUV was not a new idea. Variants of the concept were proposed decades earlier and largely dismissed as impractical, fragile, or economically absurd. To be fair, at the time, that skepticism was reasonable. EUV sources were unreliable, optics were nightmarishly complex, and throughput was nowhere near production-ready.

Fast forward to today however, and EUV is anything but experimental. It is a production workhorse that is enabling single-digit nanometer processes across all industries. Entire fabs are now built around the technology, with the machines being as much scientific instruments as they are manufacturing tools. Thanks to EUV, the semiconductor has been allowed to keep scaling in ways that once looked implausible, even to insiders.

But EUV is not a permanent solution. As the industry pushes toward sub-nanometer feature sizes, the physics becomes increasingly hostile. Going beyond the 1 nm regime is more than a matter of better optics or tighter control. At these scales, atoms stop behaving like convenient Lego bricks which can be placed in position as needed. While atomic-scale transistors can (and have) been built, they are only laboratory demonstrations, not manufacturable devices containing tens or hundreds of billions of transistors. For example, techniques like electron beam patterning can create astonishingly small structures, but they are slow, serial, and economically useless for high-volume manufacturing.

This, sadly, is where we must face the uncomfortable truth; EUV is approaching the edge of its usefulness. The technology that rescued the industry a decade ago may not be able to carry it much further, and, as a result, attention is now shifting toward whatever comes next, assuming there is a viable next step at all.

Enter X-Ray Lithography

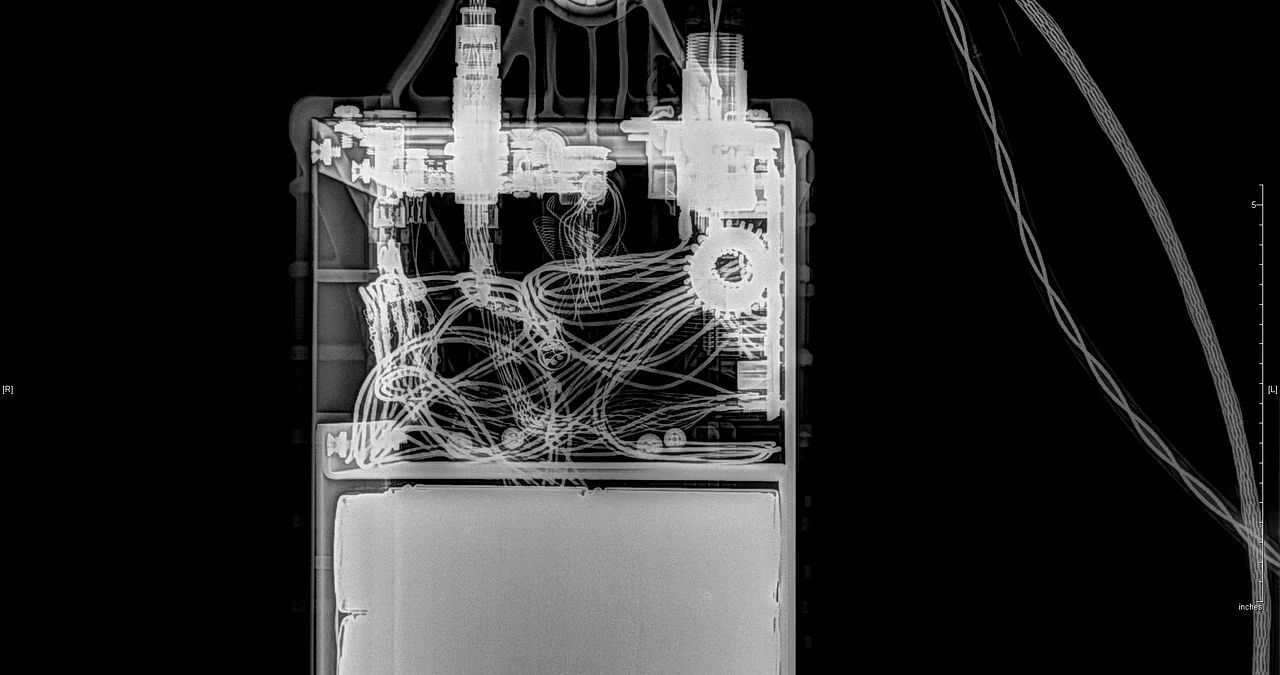

In semiconductor manufacturing, ambition tends to swing between extremes, and when incremental improvements stop working, the response is often to abandon subtlety entirely. X-ray lithography is one that fits neatly into this historic pattern, and if shorter wavelengths are the answer, then X-rays appear to offer an almost unfair advantage. X-rays operate at sub-nanometer wavelengths (between 0.1nm and 1nm), which theoretically allows for extremely fine feature definition. Ideally, this could simplify parts of the manufacturing process rather than complicate them, as with sufficiently short wavelengths, techniques resembling shadow printing become possible, where the pattern on the mask maps directly onto the wafer with minimal optical distortion. That reduces dependence on complex correction algorithms and elaborate lens systems that currently dominate EUV tool design.

Shorter wavelengths also make it easier to resolve smaller features without heroic numerical apertures or exotic optical tricks. As such, the theory is that x-ray lithography could restore a more straightforward relationship between mask design and printed result, something the industry has not enjoyed for a long time.

Unfortunately, X-rays are not cooperative in the slightest. Compared to UV, they are extremely energetic, which means they have a talent for damaging whatever they interact with. Sensitive material layers can be altered or destroyed outright, introducing defects at the exact moment precision is most critical. Generating X-rays at the required intensity and stability is itself a non-trivial challenge, and once generated, they are frustratingly difficult to manipulate. X-rays do not reflect or refract in useful ways with conventional optics, which severely limits beam shaping and control.

Then comes shielding. Containing X-rays requires dense materials like lead, adding bulk, cost, and safety complications to already complex tools. Now, each of these problems has potential solutions on paper, but taken together, they form a wall that X-ray lithography has yet to climb. This is why, despite decades of discussion, it remains largely conceptual rather than commercial.

What Happens If X-Ray Lithography Cannot Be Cracked?

If X-ray lithography never makes the leap from theory to factory floor, the future of semiconductor scaling becomes far less comfortable, with the smallest achievable feature sizes effectively plateauing around what current EUV can support. Pushing EUV to even shorter wavelengths would be an extraordinary technical challenge, likely fraught with brutal economic consequences.

Thus, when traditional scaling stalls, the industry will adapt by changing direction rather than surrendering. Chiplet-based architectures would move from being a clever optimization to a major necessity, where instead of one monolithic die, systems would rely on multiple smaller dies combined in advanced packages. Such manufacturing technologies including die stacking, heterogeneous integration, and tight coupling directly on substrates or PCBs would end up defining performance gains rather than raw transistor size.

System-on-chip (SoC) and system-on-module (SoM) designs would become increasingly important, allowing designers to extract more functionality from fixed transistor dimensions. Optical interconnects, switches, and bridges could play a larger role in addressing data movement bottlenecks, which already dominate power and performance budgets in modern systems.

None of these approaches change the fundamental size of transistors, but instead, work around it. That reality would force engineers to become more disciplined, more creative, and far less reliant on brute-force scaling. In some ways, that might even be healthy for the industry. Moore’s Law has been a generous crutch for decades, but as all good things must come to an end, so should the law that has defined the semiconductor industry since its birth.

Whether the future belongs to X-rays or to smarter system-level design remains unresolved. What is clear is that EUV, impressive as it is, cannot carry the industry indefinitely. The next chapter of semiconductor manufacturing will be defined as much by architectural ingenuity as by lithographic breakthroughs, assuming those breakthroughs arrive at all.