The Challenges With Current Memory Technologies

Modern computing systems rely on a patchwork of memory technologies, each designed for a narrow purpose rather than as a universal solution. The result is a hierarchy of devices that work together, but only because engineers have spent decades building increasingly complex bridges between their mismatched strengths and weaknesses.

NAND flash is a prime example. It’s non-volatile, capable of holding information for years without power, and it scales well for compact storage. But it suffers from low write endurance, where repeated program and erase cycles eventually wear it out. It’s excellent for long-term storage, but fundamentally unsuitable as a direct replacement for working memory.

On the opposite end, traditional magnetic hard drives (the “spinning rust” variety) remain unmatched for cheap, high-capacity storage with reasonable long-term reliability. Their flaw, however, is obvious: speed. Compared to modern processors, they are serious bottlenecks, which is why in practice, they serve as bulk storage layers, being tolerated rather than admired. DRAM provides the speed required for running software and managing active workloads, but it’s far from perfect, however, as it loses all data when power is cut. As a result of this volatility, computers need a constant flow of data back and forth between DRAM and non-volatile storage, an architectural compromise that complicates both hardware and software.

The separation of roles between these memory technologies introduces design challenges that fundamentally impact computer performance. For example, because system RAM is physically distinct from permanent storage, CPUs require dedicated I/O controllers and interfaces just to fetch data from external storage solutions. Even within the CPU, DRAM access is not fast enough, requiring additional SRAM cache layers to compensate. The result is a deeply tiered system of memory pathways, each designed to mask the shortcomings of the layer below it.

The result of all these technologies and issues is that today’s memory landscape is highly fragmented. Every technology fills a niche, but none offers a complete solution (i.e. a unified memory solution).

UltraRAM Moves Toward Volume Production

A new entrant in the memory space, UltraRAM, has moved past the laboratory stage and into industrial scaling. Unlike the incremental advances we’re used to seeing in NAND or DRAM, this technology attempts to merge their best traits: DRAM-class speed (orders of magnitude greater endurance than NAND), and long-term non-volatility. In theory, this new memory could collapse the fragmented memory hierarchy into a single device type, giving engineers the ultimate memory technology.

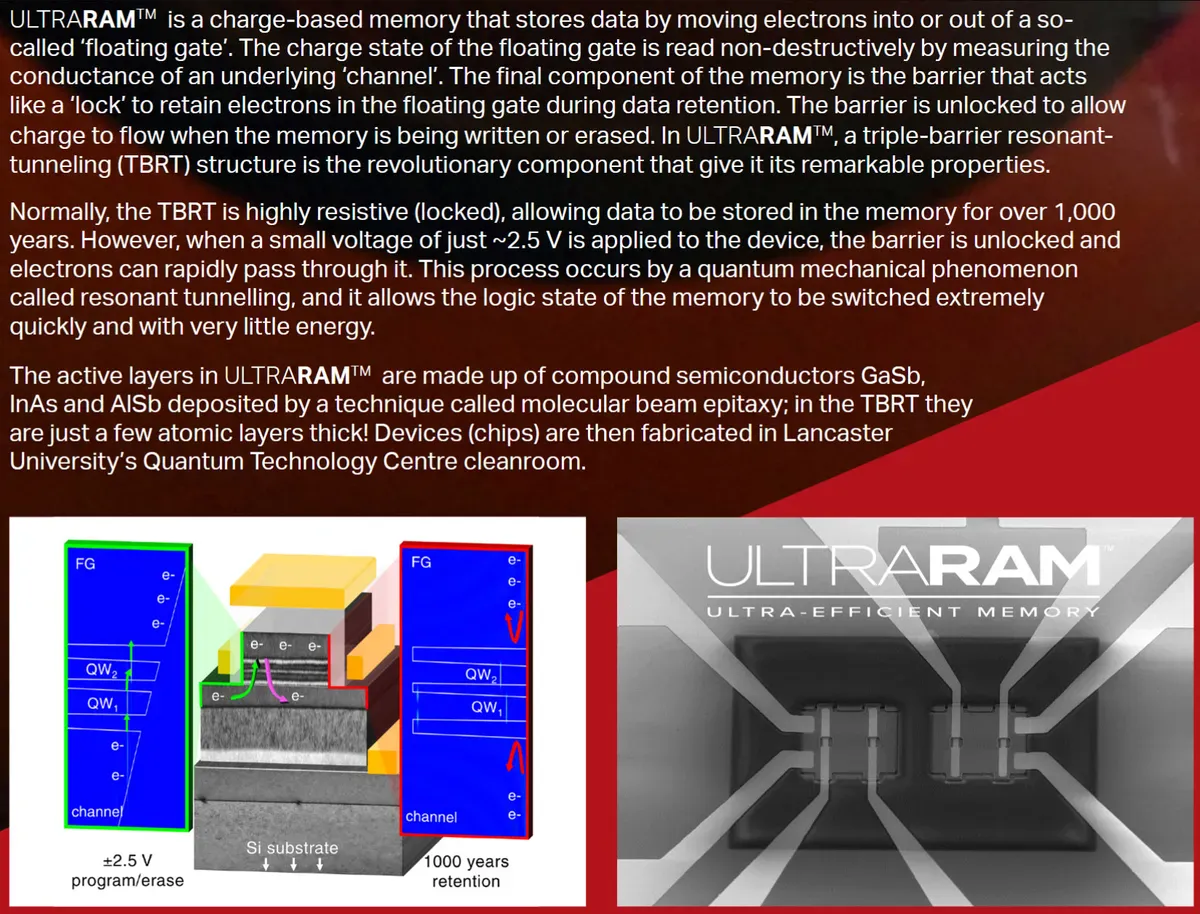

The key enabler in UltraRAM is a compound semiconductor process using gallium antimonide (GaSb) and aluminum antimonide (AlSb) grown by epitaxy. Epitaxy allows crystalline layers to be deposited with atomic precision, forming the heterostructures needed for resonant tunneling, the quantum-mechanical effect at the heart of UltraRAM’s switching behavior. After epitaxy, the devices enter more conventional semiconductor workflows, including photolithography, etching, and metallization, which all define the cell arrays and interconnects.

The key enabler in UltraRAM is a compound semiconductor process using gallium antimonide (GaSb) and aluminum antimonide (AlSb) grown by epitaxy. Epitaxy allows crystalline layers to be deposited with atomic precision, forming the heterostructures needed for resonant tunneling, the quantum-mechanical effect at the heart of UltraRAM’s switching behavior. After epitaxy, the devices enter more conventional semiconductor workflows, including photolithography, etching, and metallization, which all define the cell arrays and interconnects.

The scaling milestone for UltraRAM was achieved through collaboration between Quinas Technology and wafer supplier IQE plc. IQE developed an epitaxial growth process suitable for volume manufacturing, rather than the small-scale, research-grade runs that dominated UltraRAM’s early history. According to IQE’s CEO, this marks the first time GaSb/AlSb epitaxy has been demonstrated at an industrial scale for memory devices. On paper, the numbers are extremely aggressive, with switching energy being claimed to be under 1 femtojoule per operation, while write endurance being quoted as 4,000× higher than NAND. Additionally, data retention is projected at up to 1,000 years, which is more than sufficient for most computing needs.

Of course, moving from wafer-scale epitaxy to packaged, reliable memory devices is a long process. Yield, integration with CMOS logic, and compatibility with existing manufacturing lines will dictate whether UltraRAM is a genuine replacement technology or just another academic curiosity. For now, Quinas and IQE are preparing for pilot production, engaging with foundry partners to determine how far the process can be pushed.

Could UltraRAM Be the Future of Memory?

UltraRAM’s promise is simple: DRAM-class speed, extreme endurance, and non-volatility. That combination makes it a natural candidate for unified memory, a single pool that could replace today’s patchwork of RAM, caches, and storage. In such a system, program code, working data, and files would all reside in one space, and power loss wouldn’t mean loosing the contents of RAM, allowing machines to reboot directly into their previous state.

With scaling efforts now underway and industrial epitaxy processes established, UltraRAM is moving beyond theory and prototypes. If it works as intended while being economically viable, it could very well make most memory technologies redundant. Such memory could simplify architectures, reduce the need for separate buses and controllers, and collapse the complex hierarchy that currently exists just to mask the shortcomings of individual memory types.

That said, perspective on UltraRAM is important, as conventional memory technologies are mature, reliable, and relatively simple to manufacture. DRAM and NAND may not be perfect, but they benefit from decades of refinement, enormous fabrication infrastructure, and well-established supply chains. UltraRAM, by contrast, is still new. Even if it delivers on performance claims, cost, yield, and ecosystem adoption will dictate its fate.

So while it’s unlikely UltraRAM will sweep in and replace DRAM and NAND in the immediate future, the timing is interesting. Current CPU and system architectures are straining against the limits of today’s memory hierarchy, and demand for a more efficient approach is growing. If UltraRAM proves manufacturable at scale, it may well become the technology that pushes the industry to rethink how memory and compute are integrated.